- The Flytrap

- Posts

- If We Valued Sex Workers, the Outcome of the Diddy Trial Would Have Been Different

If We Valued Sex Workers, the Outcome of the Diddy Trial Would Have Been Different

What if Diddy’s victims were protected by labor laws instead of relying on the lack of justice of a sexist trial?

🛑 HOLD UP THERE, FRIEND! READ THIS FIRST! 🛑

WE’VE MOVED! You’re reading this on an archived version of The Flytrap that exists only to preserve links to content we published before August 27, 2025.

To get new editions in your inbox every week, subscribe over at our new home on Ghost. (And if you’re already a paid Flytrap subscriber, you should have experienced an almost seamless transition to be able to read our content on Ghost, but if you aren’t able to do so, please reach out to the Flyteam at [email protected].)

While we have you: The Flytrap merch store is now open! Get dripped out in the latest Flytrap merch or buy a poster from our collection.

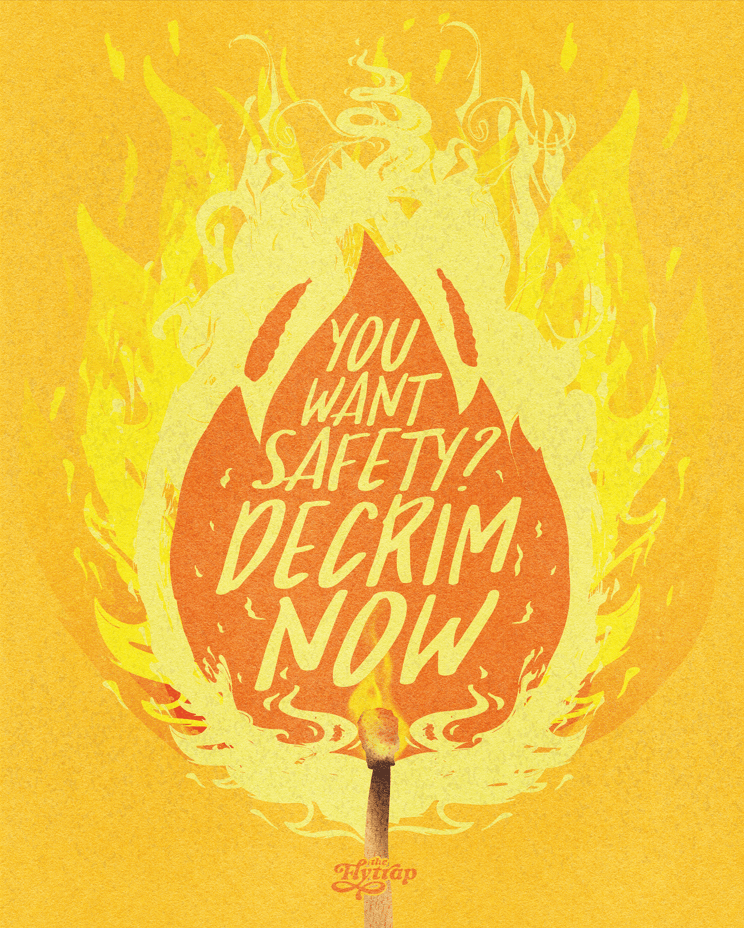

Credit: rommy torrico

After eight months of pre-trial incarceration, endless speculation, and millions of dollars spent on attorneys, the United States of America v. Sean Combs trial came to an unsatisfying conclusion earlier this month. Combs, a hip-hop mogul with endless access to fame, wealth, and power, was facing a life sentence if convicted of the five counts charged by the Southern District of New York. Despite compelling testimony from several of his victims, including his former girlfriend Cassie Ventura, the jury ultimately acquitted him of three of the most serious charges, including sex trafficking, and convicted him on two counts of transportation to engage in prostitution.

Combs is now facing 20 years, with legal experts estimating that he will likely be sentenced to less than five years and will have that time reduced by 13 months because he was denied both pre-trial and post-trial bail. It is certainly a disappointing outcome, especially for those of us—me included—who perceived this as the proverbial first domino in the long overdue reckoning owed to Black women in hip-hop.

Become a Member to Keep Reading

Join fellow fans of independent, worker-owed feminist criticism against the algorithm.

Already a paying subscriber? Sign In.

Members receive:

- • 🌱 Fresh Flytrap posts every Tuesday

- • 📰 Full access to our entire back catalog

- • 💫 Discounted admission to Flytrap classes and events

- • 🌈 The satisfaction of supporting independent feminist media

Reply